Former G.I.s Describe their Life as Expats in Germany

Like many readers of Driftless Now, I performed my military service during the Cold War in Germany. And, like thousands of lonely young men, far from home, I fell in love with and married a German girl. Upon my discharge from the Army, Gerdi followed me to the United States, where we lived in Chicago, raised two children, and experienced the joys and challenges of married life until her untimely death in 1984.

Thirty years into a second happy marriage, questions still prey upon my mind: How might life have been different if Gerdi and I had settled in Germany, rather than in the U.S.? How would I have coped with the barriers of language, culture, and employment in a foreign country? How would our sons have fared in the German educational system? Would Gerdi have experienced less financial and emotional strain living and working in her home country? Would greater peace of mind, combined with German socialized medicine have enabled her to beat the cancer that took her much too soon?

In 2017, with the full support of my understanding wife, Barb, I traveled to Germany to seek answers to these questions, which had plagued me for decades. I would locate and interview former G.I.s who had married German women and elected to make Germany their permanent home. My students at Madison Area Technical College supported this project by brainstorming a list of 83 questions about social, legal, and employment conditions faced by American expats in Germany.

Over 14,000 retired U.S. military personnel reside in Europe; the greatest number of these are in Germany. In most cases, these are men who married German women. During my three-week stay, I managed to interview 16 veterans, many of their wives, and one German woman who is divorced from an American military officer. They ranged in age from their forties to their seventies. Most were retired but living active lives, traveling, and volunteering. Others were employed in a variety of professions. Likewise, the marital status of the men (and woman) I interviewed varied from single to twice or thrice married to over five decades of wedded bliss. All but one live in or around Nuremberg, the city where I was stationed as a young G.I. five decades ago.

Love and Marriage

When a man loves a woman

Can't keep his mind on nothin' else

He'd trade the world

For a good thing he's found…

--Percy Sledge

The question most frequently posed by my students was, “Why did these veterans and their German wives decide to make their homes in Germany?” After all, weren’t German girls eager to get to America, where “the streets were paved with gold?” That common misconception may have been the case in post-war Europe, when people were starving there, but by the 1960s and ‘70s, life was pretty good in Germany. The couples I interviewed included professional women: teachers, nurses, and business owners. As Claudia Radczun-Polk, a teacher, put it, “I never considered moving to Texas with my American husband. I had invested years of education to attain the credentials necessary to teach in Germany. If I moved to another country, I would have to start over again.” Family, friends, jobs, and property, along with language, culture—everything they had known—bound these women to their homes.

However, a young man, pierced by Cupid’s arrow, will go anywhere, do anything to be with his beloved. For many of the men I interviewed, that meant “re-upping” (reenlisting) in the Army—the only way they could remain in Germany with their “Schatzies.”

Ironically, once they were in the clutches of Uncle Sam as “lifers” (career soldiers), their choice of assignment was beyond their control. They could extend their tour of duty in Germany for awhile, but Vietnam was calling, as Dwight Johnson learned. “Beating the bushes” with the 101st Airborne in Vietnam, he was wounded in action. After Vietnam, Dwight’s perspective on life changed, he told me—a sentiment echoed by Tyrone Wylie and Steve Milke, who survived Vietnam and opted for the comparative comfort of Army life in Germany.

As Army wives, some of the women followed their husbands, at least to non-combat zones. Ute Starr’s introduction to “America the Beautiful” was Dugway Proving Ground, Utah, an isolated spot in the desert, 85 miles from Salt Lake City. A qualified nurse in Germany, Ute had to clean barracks while studying for her American nursing credentials. Then, as an RN, she responded to the April 19, 1995 Oklahoma City bombing perpetrated by Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols. She returned home around midnight, having given a badly needed break to the other Red Cross workers and helping to locate ten more bodies in the rubble, even as additional explosives were being found in the building. Her bravery and dedication complimented that of her husband, David, who served two tours of duty in Korea.

The Starrs settled in Florida after twenty-plus years with the military. When David’s father died, he decided that, having followed him all those years, Ute deserved to be with her own ageing parents. There was another reason for their move to Germany: David had suffered a serious injury in the service when his tank went over a cliff during maneuvers. Neither the military doctors nor the Veterans Administration had been able to offer relief over a seven-year period. Since Ute was still registered under the German healthcare system, David would be covered. When the Starrs relocated to Germany and David saw a physician, his condition was diagnosed, and he was scheduled for surgery within hours. The ten-day stay in the hospital cost David $100. He was amazed at the difference in quality and cost of treatment in Germany, compared to the U.S.

Several other veterans cited healthcare as a prime reason for their choice to live in Germany. Asked what Germans think of the United States, Larry Townsend replied as follows: “Some think our [healthcare] system is not working. Everybody over here has to have medical insurance. My company pay half, and I pay the other half—$250 a month, as long as you work. And once I retire the state will pay the whole $500. It's not like [my mother in] America. She has to call the insurance company first and say, ‘I'm sick today, please get me an appointment.’ They find the cheapest doctor to save money. They call back and tell my mother she has an appointment Friday—in three days, but she's sick today.”

Mrs. Townsend’s employer in California pays $700 a month for her insurance. In one instance, the family had to cover her ambulance bill of $1,100. By contrast, Larry’s pills to control the effects of bone marrow cancer cost 300 Euros each, and he has to take 30 pills a month, but he pays nothing out of pocket. Larry told of a friend in the U.S. who has a similar condition but gets no help from the VA. The veteran relied on Obamacare and expressed hope that the Trump Administration would not take it away.

While it is generally conceded that the financial side of healthcare is broken in this country, some argue that the quality of treatment here is the best in the world. I put that question to Bob Beckham, a former Army captain, who described in great detail (and considerable humor) the care he received for a compound fracture incurred skiing in the Alps. “Where do you go for the best medical care?” he replied, “I've lived in Germany and America and different places. If you need specialized medical care, it depends on what you need. Heart, lung, brain, you're going to get the best in America. Leg, knee, shoulder, you're going to get the best in Austria. If you need basic medical care, you're going to get the best in Germany. I take my card, walk down to my doctor five times a week. I can see him five times a week. Cost free, okay? if I need medicine, it cost me maybe five Euros a prescription. Sometimes it cost me nothing for a prescription.”

The impression I received from my interviews is that healthcare is the number two reason for their decision to live in Germany, rather than in the U.S. The number one reason is love. The most delightful part of my research project was hearing the stories of couples like the Starrs and seeing how they keep their marriages alive with devotion, sacrifice, fun, humor, and even fighting.

Don Norris was 17 when he arrived in Germany in 1958. He met Sigrun 22 days later.

“My parents had a house right next to the [U.S. Army] gate,” Sigrun recalled. “We also had a dog, an Irish Setter. We called him ‘Schlumpy.’” Sigrun explained that Schlumpy was well known by the Americans because when he got out of her family’s garden, he would chase birds and rabbits on the Army base. The MPs would bring him home. One day, Don was walking outside the base with a friend, taking pictures in the neighborhood. It must have struck the 17-year-old boy as exotic, compared to Arkansas. That’s when he spotted Sigrun and Schlumpy. “Ja, and then, of course, he started talking immediately,” said Sigrun. “‘Beautiful dog,’ I think he said, and ‘May I take a picture of your dog?’ I tied the dog to a bush, and I said, ‘Now you can take a picture.’ But he didn’t want the dog; he wanted a picture of me, I think.”

Sigrun’s parents discouraged the romance, even sending her to live with a relative in Northern Germany. Don persisted with the ardor of a young Romeo, writing letters every day, until his Juliet relented. He even swam across the wide Main river to join her at her family’s campsite. (Her uncle said at the time, “Wait—in 20 years, he won’t jump across a mud puddle to get to her.”)

The rest of the story—55 years of wedded bliss—emerged from listening to Don and Sigrun at their cheerful kitchen table. They held hands and shared secret smiles when recalling special moments from the past: children’s accomplishments, their community involvement as volunteer firefighters, members of a choir, and organizers of charity events. They laughed when describing a humble village home with an “indoor outhouse” (“Plumpsklo”) when they lived as poor newlyweds and heated water on a wood stove for the baby’s bath.

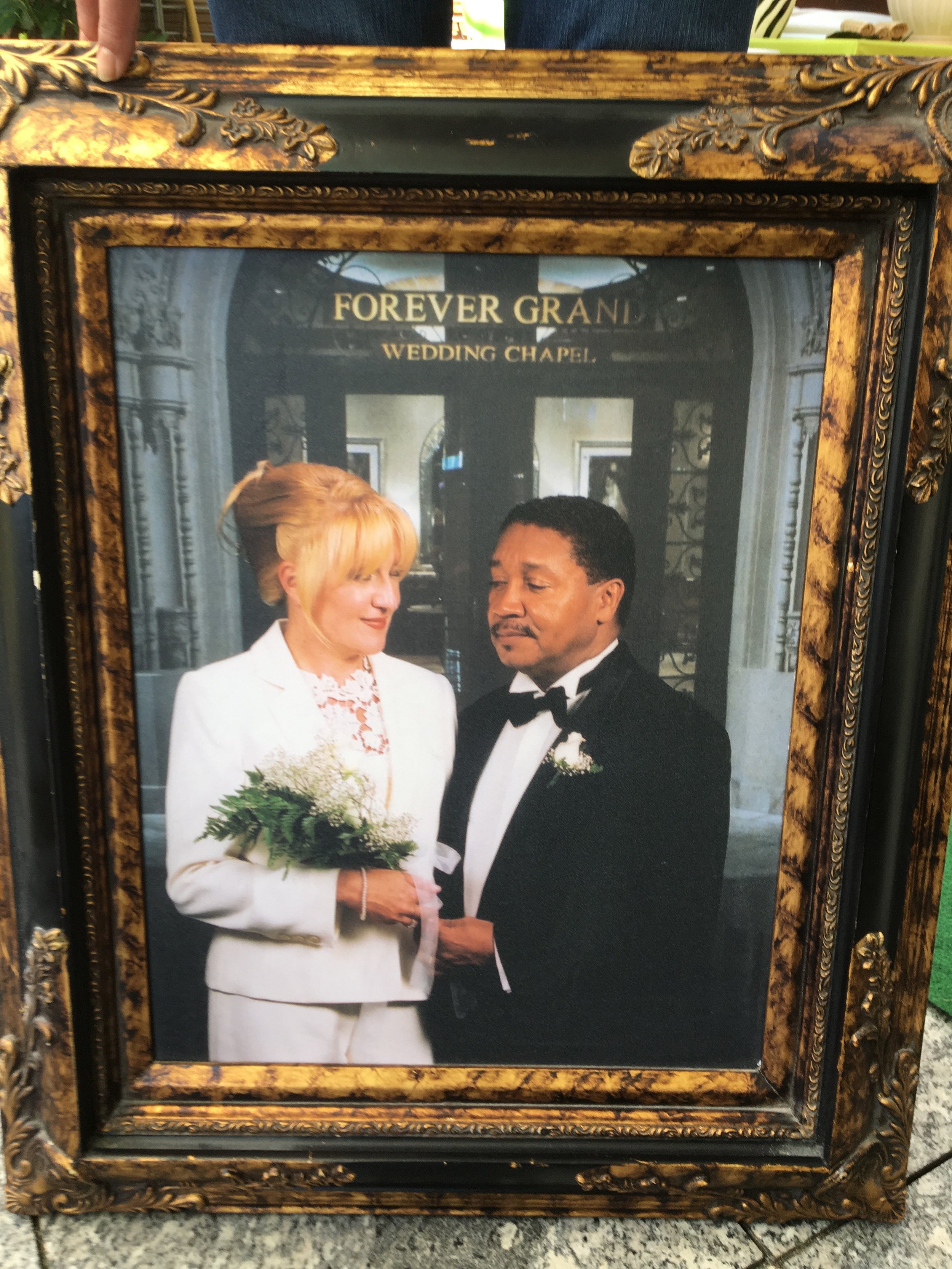

Happily-married couple Fred and Inga Rivera fuel their love with humor, David and Ute Starr with devotion to God, Nick and Gerlinda Nolte with mutual interests, and Dwight and Erika Johnson with fair fighting. I learned something about love from my encounters with each couple. My conclusion was that every person and every couple are unique. It would be impossible to infer from their experience how my own marriage to Gerdi would have been different if we had lived in Germany.

Some of the guys I interviewed shared horror stories about their marriages to German women. One gentleman in particular, who had held a high-level job with the American government, was ruined, financially and emotionally, by a spiteful ex-wife and her combative lawyer. He said that in Germany, the courts take the word of a German citizen over that of a foreigner. Accused of kidnapping his daughter because he renewed her American passport, he lost his security clearance (and job) and was reduced to collecting bottles for the deposit in order to survive. His precedent-setting case even made it to the Supreme Court of Germany. The leather-bound Supreme Court decision he showed to me was impressive, even though I could make out nothing of the legalese.

Civilian Work

Every former G.I. I spoke with had experienced barriers in post-military employment. Unless one is fluent in German, certain opportunities are closed. The proper credentials are required for most jobs and professions. Demonstrated skill alone is not enough. The German educational system prepares students for employment at various levels. For example, “Mittleschule” (middle school), grades five through nine, puts students on track for trades, such as butcher, baker, etc. Foreigners require a work permit.

Many of the men I interviewed had retired from the military after 20 years of service. Still young, they went to work for an American agency, such as the Army or the Armed Force Exchange Service (AAFES), commonly known as the PX. However, AAFES rules required American employees to rotate back to the States periodically, an impediment to home ownership and a stable family life.

Some of the veterans had “worked the system,” as soldiers and later as civilians, to maximize their time in Germany. One gentleman explained how he had gotten a hardship transfer back to Germany from Fort Bliss, Texas, citing his in-laws’ failing health. Another vet, Fred Rivera, had been able to remain in Germany as a civilian employee by “bouncing” from one agency to another: the (American military) post office, the PX, etc.

Still others went directly to the German economy for employment. Often, those jobs were menial, skirting the standard system of certification. In some cases, an ex-G.I. could work for an American-owned restaurant or other business. Neil Morrison, for example, worked for a moving company, as a laborer constructing bleachers for temporary exhibitions, and as a bartender before settling into the manufacturing job he has held for the past 15 years. To get a permanent job with an established firm typically required the personal recommendation of an insider—a German employee known to management. Smaller, family-run businesses in particular, may be willing to circumvent the traditional apprenticeship system of hiring if a candidate proves his mettle on the job. Nick Nolte was able to transfer his military skills as a diesel mechanic to become a valuable member of a small truck repair facility. Dubious at first because of Nick’s halting German, the owner was won over by the American’s proficiency as a mechanic and his rapidly improving language skills.

As with immigrants the world over, some American expats become entrepreneurs. They may provide services to the military community, for example, or even run a bar, as Norbert Issak did when his lack of German work credentials presented a barrier to employment. He and his German girlfriend ran the “Ludwigstrasse Social Club,” modeled after a typical cowboy bar, for 29 years. The Wild West motif was transplanted to his present apartment, adorned with saddles, six shooters, and a life-size cardboard John Wayne.

The Expat Life as an Escape

The military offers a way out of poverty and adversity. For some African-Americans, an overseas assignment was an escape from de facto segregation and ghetto life. Larry Thompson grew up “straight outta Compton,” the second of eight children. His older brother was friends with a founder of the notorious Crips street gang. While Larry was stationed at Fort Campbell, one of his younger brothers was gunned down by a rival gang member. On emergency leave to attend his brother’s funeral, he and his older brother spotted their brother’s murderer. Larry’s brother handed Larry a gun and said, “You know what you gotta do.” When Larry objected that he was trying to live a clean, military life, his brother took out a second gun and told Larry that if he didn’t shoot their brother’s assailant, Larry himself would die. (I asked Larry, of course, if he had shot the rival gang member. He responded that, yes, he winged the guy, but the two met 15 years later and had “a good talk about the old days.”)

Racism, while not as blatant as in the United States, is alive and well in Germany. Right wing neo-Nazies are increasingly active, especially in the eastern, formally Communist, part of the country. Larry Thompson related an incident in which he was referring a basketball game in Chemnitz. The home team lost, and from the stands came a chant, “Kill the N…!” Larry had to be escorted out of town by the police. Even in Nuremberg, he has encountered drunken skinheads who objected to seeing him with his German wife.

In general, however, the veterans I interviewed—Black, Hispanic, or White—were quite pleased with everyday life as expats in Germany. They praised the healthcare and social welfare system, public transportation, the cleanliness and safety of Nuremberg, and the many festivals that bring people together throughout the year. Their political views about European and American affairs mirrored those of their compatriots back home. Many thought that German Chancellor Merkel’s policies on immigration were too liberal. While they favored some of the policies of the White House, they were embarrassed by the president’s behavior. Despite current tensions with the Trump administration, they felt that most Germans genuinely like Americans. They missed their families and made an attempt to get home as often as they could afford the trip. They do travel in Europe frequently, as a two-hour drive can find them in a country with a different language, different food, and different culture. They believe that their experience living in a foreign country has helped them to grow. As one gentleman put it, “not just to grow up, but to grow out.”

Robert Potter, of Hillsboro, Wisconsin, is author of Patriotic Expats: Former G.I.s Describe their Lives in Germany, an e-book available for download on Amazon.